English Title: Invisible Life Original Title: A Vida Invisível Year: 2019 Genre: Drama Country: Brazil, Germany Language: Portuguese, Greek Director: Karim Aïnouz Screenwriters: Murilo Hauser, Inés Bortagaray, Karim Aïnouz based on the novel by Martha Batalha Music: Benedikt Schiefer Cinematography: Hélène Louvart Editing: Heike Parplies Cast: Carol Duarte Julia Stockler Gregório Duvivier António Fonseca Bárbara Santos Fernanda Montenegro Flávia Gusmão Maria Manoella Flavio Bauraqui Cristina Pereira Gillray Coutinho Nikolas Antunes Eduardo Tornaghi Rating: 7.9/10

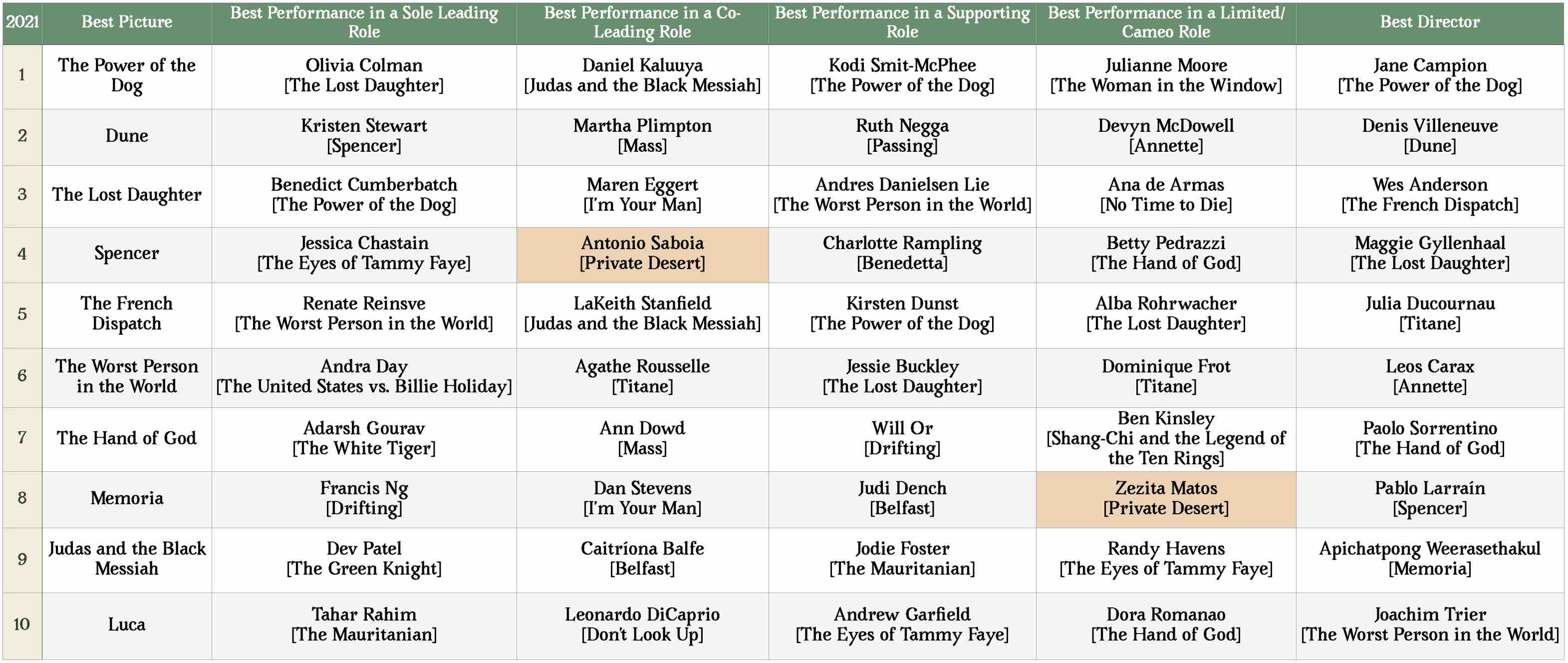

English Title: Private Desert Original Title: Deserto Particular Year: 2021 Genre: Drama Country: Brazil, Portugal Language: Portuguese Director: Aly Muritiba Screenwriters: Aly Muritiba, Henrique Dos Santos Music: Felipe Aryres Cinematography: Luis Armando Arteaga Editing: Patricia Saramago Cast: Antonio Saboia Pedro Fasanaro Thomas Aquino Zezita Matos Cynthia Senek Luthero Almeida Laila Garin Otavio Linhares Sandro Guerra Flavio Bauraqui Rating: 7.4/10

Two acclaimed Brazilian pictures knuckle down to unpick our society’s inveterate cankers with force, style and verve, Karim Aïnouz’s INVISIBLE LIFE butts head against ossified paternalism and sexism in the 1950s, meanwhile Aly Muritiba’s PRIVATE DESERT explores the possibility of emancipating masculinity from its jaundiced monotony through an unexpected love story between a macho policeman and a transvestist twink in the present day. INVISIBLE LIFE is, first things first, saturated with highly seductive and alchemical color-way, Aïnouz and his DP Hélène Louvart ensorcel audience with his uncanny configuration of chromatic vividness to give a retro-infused Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s. The film is so gorgeously lensed, even in the most pedestrian space, unexpected color pops up to reflect its mood and vibes, all balanced with impeccable harmony and lusciousness. Two sisters, Eurídice (Duarte) and Guida (Stockler), their care-free adolescent life is perversely asunder when Guida returns with a bun in the oven after her impulsive elopement with a Greek sailor. Kicked out of the family by their father Manoel (Fonseca), Guida is shucked to believe Eurídice has left to Vienna to study music, and Eurídice doesn’t even know Guida has returned, thinking the latter stays in Greece and abandons her family, she even hires a skip-tracer to find her whereabouts. A belatedly reunion is what drives the narrative trundling along the repressive environment, in one moment, during the Christmas season, the two beloved sisters are both physically present in the same restaurant with their respective kids, but before they could lay their eyes on each other, Guida is chased away by a sexist waiter, such a close call, Aïnouz teases us serendipity might in the works as a familiar cinematic trope, risking letting our patience wear thin. It is through Guida’s incessant letters to Eurídice that we see their respective lives pan out, Eurídice gets married and becomes a mother, but doesn’t give up her dream as a pianist, much to the annoyance of her husband Antenor (Duvivier), who only wants an angel at home. Guida has a tougher road on her own, abandoned and miserable, she turns tricks to survive, but eventually finds her real family with Filomena (Santos), an ex-streetwalker and soon in order to inherit Filomena’s property when she passes away, Guida changes her name, consequently and permanently severs the family tie. So is there any scintilla of hope left for a reunion? INVISIBLE LIFE is a tactfully ideated, conceptualized and actualized piece of filmmaking, minor plot contrivances aside (a gnawing bug is that Guida could get wind of Eurídice’s news from any relatives who have attended the latter’s wedding, yet, she obdurately believes her sister is faraway in the Northern hemisphere, living her dream as a musician), it attests to be food for thought: two young girls’ dreams are shattered by their closest members of the sterner sex, are all the males complicit? The cast is stupendous, in the dual leading roles, Duarte and Stockler contend with their resolute, poignant interpretation of their characters, with the former projecting a more blunt, smoldering interiority while the latter manifesting tons of emotional voltage from her petite figure, both sisters are victims, but they don’t take it without a fight. INVISIBLE LIFE soundly packs a punch in the end, much on the strength of Montenegro as the aging Eurídice, only after the death of Antenor, the truth of Guida finally comes out, Montenegro is tremendously touching to rattle our emotion with tears first, then elation in the next breath, it is a rather soapy ending, but she single-handedly makes it worthwhile. PRIVATE DESERT has another monster to battle, the preponderance of heterosexual masculinity is embodied robustly by Daniel (Saboia), whose job as a policeman is scuttled by a bout of violence which leaves one victim in coma. What adds insult to injury, the woman he dates online for a while, Sara, suddenly ghosts him. In the spur of the moment, he drives from Curitiba to Sobradinho to look for her, the self-claimed love of his life, only to be forced to take a hard look on his mono-sexuality and male pride, Sara is actually Robson (Fasanaro), a young man who has everything to lose if his drag persona is brought into open. Shot intensively close to its protagonists, first Daniel then Robson, who comes to the fore during the second half of the film, PRIVATE DESERT is a character study fashioned with minute attention and brutal honesty. Daniel, extraordinarily played by Saboia with imposing virility and intricate mentation, is a man in jeopardy, ministering to a father ailed by dementia (a silent Luthero Almeida whose expressions speak louder than words), facing an imminent investigation might put him in jail, his pent-up frustration and anxiety needs to be canalized out for the sake of his well-being, so Sara becomes his only salvation, but it is exactly his savage, primordial inclination to violence scares her off, because Sara fears to be a victim when the hammer blow hits Daniel. The Robson/Sara dilemma has a more predictable aspect in it, religion-backed therapy is scorned, genuine friendship and family support is heartfelt (Zezita Matos brings off an endearing persona as Robson’s seemingly stern grandmother), Fasanaro’s drag act is less mesmeric as we are led to believe, but he holds his own as the more courageous one, who eventually inspires the case-hardened Daniel to change. However, Daniel’s turnabout feels sketchy and is insufficiently spelt out, Muritiba applies a tacky sex scene to vicariously bear out Robson’s irreplaceability to Daniel, which overrides the blinkered male/female distinction, then, just when Robson feels dismally dejected, he can be lifted up to finally embark on a new journey from the dead-end status quo, and it is a relief that the pair’s happy ending is not staying together but both find new courage and purpose from each other, to brave their kismet paved with impediments ahead, they might be reunited in the future, but at that particular moment, Muritiba is markedly astute to leave the story as where it is, a compelling, edifying story about sexual fluidity that hits like a bang to navel-gazers, but serves as a delectable dish to the queer cinema. referential entries: Kleber Mendonça Filho’s AQUARIUS (2016, 8.3/10); Aluizio Abranches’ FROM BEGINNING TO END (2009, 6.7/10).