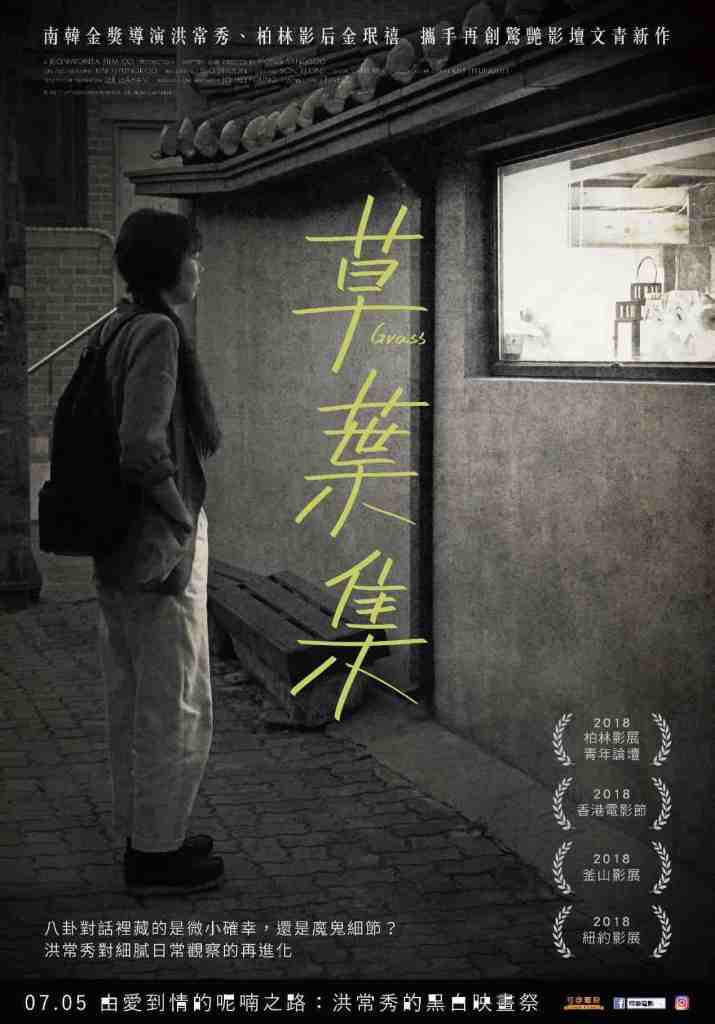

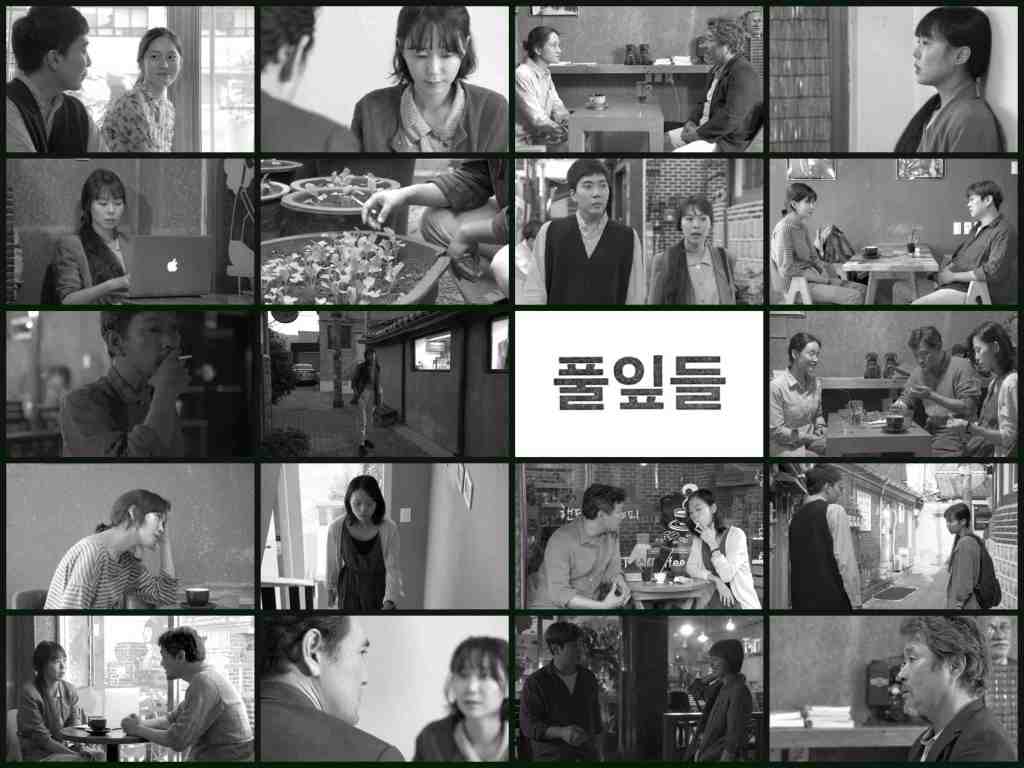

Title: Grass Year: 2018 Genre: Drama Country: South Korea Language: Korean Director/Screenwriter: Hong Sang-soo Cinematography: Kim Hyung-koo Editing: Son Yeon-ji Cast: Kim Min-hee Jung Jin-young Kim Sae-byuk Gi Ju-bong Seo Young-hwa Gong Min-jung Ahn Jae-hong Shin Seok-ho Ahn Sun-yeong Lee You-young Kim Myeong-su Rating: 6.7/10

English Title: Hotel by the River Original Title: Gangbyeon hotel Year: 2018 Genre: Drama Country: South Korea Language: Korean Director/Screenwriter: Hong Sang-soo Cinematography: Kim Hyung-koo Editing: Son Yeon-ji Cast: Gi Ju-bong Kim Min-hee Kwon Hae-hyo Yoo Joon-sang Song Seon-mi Shin Seok-ho Rating: 7.1/10

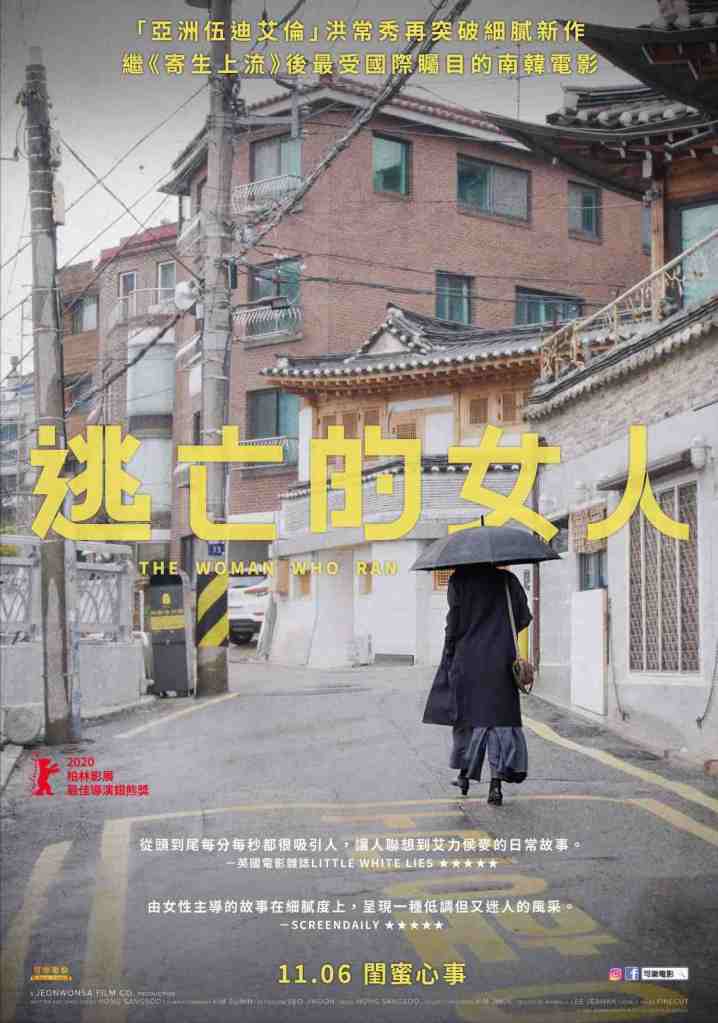

English Title: The Woman Who Ran Original Title: Domangchin yeoja Year: 2020 Genre: Drama Country: South Korea Language: Korean Director/Screenwriter/Music/Editing: Hong Sang-soo Cinematography: Kim Su-min Cast: Kim Min-hee Seo Young-hwa Song Seon-mi Kim Sae-byuk Kwon Hae-hyo Shin Seok-ho Lee Eun-mi Ha Seong-guk Rating: 7.2/10

A triad of Hong Sang-soo’s “conversational pieces”, released in 2018, GRASS and HOTEL BY THE RIVER are blanched monochromatic constructs seemingly borne out of aleatory orchestration, then two years later, THE WOMAN WHO RAN, shot in pastel hue, with Hong’s muse Kim Min-hee wearing a new curly hairdo, engages her with a more coherent narrative and comparatively, lets on a more gratifying allure. Hong’s prolific output, actualized by practicing his art in a contained scale, fixating on the same characters (artists) and themes (man-woman interpersonal relationship chiefly), might lends an impression that the same story has been done ad nauseam, as well as his distinctive shooting style, long takes of often symmetric two-shoots of people conversing, pulling focus and zooming in on one interlocutor with the camera staying static, and Hong’s partiality towards scenes of food-partaking and alcohol-toping. Thematically, Woody Allen and Éric Rohmer are two most mentioned names Hong is compared with, but aesthetically, he is more austere, and resolute. GRASS’s main set is a languorous coffee shop, Kim Min-hee plays A-reum, who quietly sits in the corner and eavesdrops sundry conversations of other patrons, and is mildly baffled when one of them approaches her for a rather audacious favor. He repeatedly extols her as “remarkable”, but his request is simply beyond the pale. Only during the more familiar situations with her brother, who introduces his new girlfriend to her, A-reum’s personal side and sharp edge emerge, superficial courtesy impaled by outright exasperation, who doesn’t have a button shouldn’t be pushed. Clocking at 66 minutes, GRASS operates on a meandering, desultory fashion that occasionally implies these personal conversations (covering dark subjects of bereavement, suicidal attempt, aftermath of a suicide, writer’s block and financial misery) are stories typed down by the woman on her laptop, which she re-enacts at will. Compiling itself in a portmanteau structure, GRASS can be viewed as capsule samples of Hong’s perennial preoccupations, but in HOTEL BY THE RIVER, a bifurcating storyline ritualistically separates the gender dichotomy for the most of time. A reconciliation between a father and his two estranged grown-up sons concurs with a consolatory rendezvous of two female friends, one of which is A-reum again, who has just experienced a devastating break-up.

It is not characteristic for Hong to dwell on the topic of filial obeisance, or father-son rapport. Young-hwan (Gi) is a poet of note has reunion with his two sons Kyung-Seoul (Kwon) and Byung-Soo (Yoo). But they often miss each other, a motif runs through the movie. When they communicate face to face, it is the usual platitude of pleasantry mingled with guilt-blaming. But Young-hwan has no remorse for deserting his family, the reason of this meeting in the hotel near Han River where he stays is simply a valediction because he has a strange premonition that his days are numbered. He just wants to know his two sons are all fine. Meanwhile A-reum (Kim) stays in the same hotel and is consoled by her friend Yeon-joo (Song), showered in post-breakup blues, the two just laze around in the hotel room to while away time. When they finally go out for dinner, they end up in the same restaurant with the father-sons trio, eavesdropping the latter’s heated convos, A-reum seems to forget her own trouble, and when Young-hwan approaches them eventually, he recites them a poem about “unable to leave” and mystery garnishes the film’s (preordained) ending. A sublime snowscape foregrounds the picturesque allure of HOTEL BY THE RIVER, the lackadaisical story is seasoned with personal quirks and sheer coincidences (the transference of the ownership pf the same automobile is an extraneous contrivance), but the anemic, languid atmosphere actually conduces to the film’s wintry background and insouciance toward morbidity, it is the ending of a man’s existence versus the ending of a relationship, both Young-hwan and A-reum manage to attain a philosophical presence of mind to deal with the demise, and for that matter, Hong lands on his feet nicely.

THE WOMAN WHO RAN ditches the gender impartiality, Kim Min-hee plays a (self-professed) happily married woman Gam-hee, visiting her old friends, first Young-soon (Seo), a meek divorcée living a rural life with her tomboy roommate, then the unmarried, free-spirited Su-young (Song), who is well-to-do and urban-like, and finally an unexpected encounter with Woo-jin (Kim Sae-byuk), the third party who once broke the relationship of Gam-he and Mr. Jung (Kwon), and who is still married to the latter. A triptych serenely scrutinizes “female existence” through an apparently disinterested outsider’s perspective, the feminine rapport plumes through pleasantries and badinage (even blindsided by Woo-jin, Gam-hee seems imperturbable and have let bygones be bygones), only interrupted by the intrusion of the sterner sex. Three male characters are all shown with their backs to the camera in their brief appearances, and their respective conversations all winds up in a misaligned communication, it is man’s “self-centered bluntness” that antagonizes women and creates discomfiture and tension, as claimed by Hong. Three states, whether divorced, unmarried or married, none is perfect for a woman, each has its own pitfalls and perks, that amounts to common knowledge. As for Gam-hee, what runs underneath her “happy marriage” guise is some undertow inaccessible to viewers. Kim Min-hee can telegraph emotional shadings in a heartbeat, but cumulatively, she hardly step out of her comfort zone in Hong’s conceptualization of an “every woman” to his liking, all her characters are consistently cerebral, coy, sensitive and prone to keep one’s own counsel. Gam-hee is the woman who runs in the end, but also the woman who ran long before that, ensconcing in front of a silver screen is her security blanket, and in Hong’s cinema-verse, it is “the” inner sanctum of ultimate peace and contemplation, something his oeuvre tries to emulate in perpetuity. referential entries: Hong Sang-soo’s THE DAY AFTER (2017, 6.9/10); ON THE BEACH AT THE NIGHT ALONE (2017, 7.6/10).